Resist tying and dyeing on threads to be woven is called ikat in much of the world. The technique is also known as mud-mee in Laos and Cambodia, and as mat-mi in Thailand.

Weavers in northeastern Thailand create some of the most stunning mat-mi patterns with cotton threads and natural indigo dye. Sometimes the artisans who bind the patterns into the threads are the same as those who will dip those threads into the dye, and weave the final product, but other times artisans become specialists in one step of the cloth production. Whether they use cotton or silk thread, the ikat tying and dyeing processes are essentially the same.

The friend with me below does all the processes herself, from binding off the white cotton threads to dyeing and finally weaving the finished cloth. See below for her labor-intensive and ingenious methods.

Creating the ikat dyeing pattern

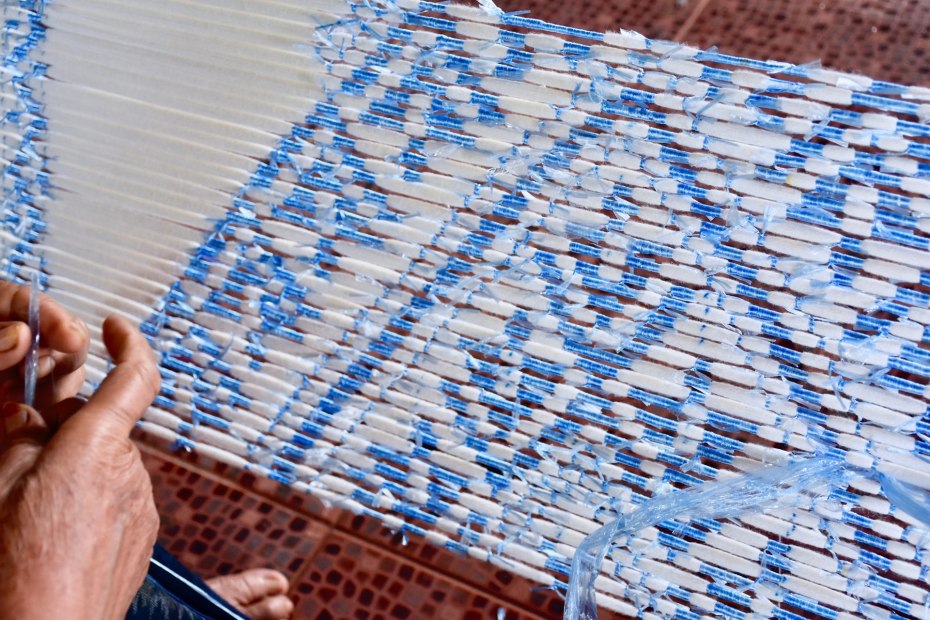

The next step in the weaving process for both silk and cotton ikat is arranging the threads tautly on a frame and marking them with the design to be dyed, left. Some weavers use a marking pen or a brush and ink, to mark their patterns on the threads. Following the lines traced onto the threads, they tightly bind the threads in the places they want protected from the dye. Some people use plastic twine, strips of plastic bags, Scotch tape, or anything waterproof that will not let the dye penetrate the fibers.

Either warp or weft threads, or both, may be dyed with patterns before weaving. Cotton mat-mi in the northeast is usually weft ikat. Finally the bound threads are dipped several times into indigo dye, then hung up to dry, as in the middle photo below. Dyers in this area make their own indigo baths, from leaves and fermenting fruits such as mangoes or star fruit, and limes to add acid. With use over time, a dye batch thickens as it evaporates, and the dyer adds more water to the slurry, to keep the mixture alive.

Dyeing the threads

In the case of mat-mi in northeast Thailand, commercial cotton thread and ‘home-brewed’ natural indigo plant dye are used (making navy blue threads where the dye penetrates). The dye process is finished after one or more dips into the blue dye. In other places, dyers use may unwrap some of the bindings and use a brush to paint another color in some of the white spaces. Then the cloth ends up as navy and white with accents of perhaps red or green, in the sections painted with liquid dye.

(Silk ikat from this area often has finer, smaller patterns dyed into both the warp and the weft, thus making double ikat, a subject for another day.)

After the dyed threads are dry, the wrappings are undone and the lengths of thread are wound onto a large bamboo wheel, then onto small bobbins, in the exact order for weaving. Finally the weaver uses the bobbins for the weft, sometimes changing the weft pattern and weaving several different designs along the length of the warp, as seen below. So as you can see, a piece of blue and white ikat cotton cloth has gone through many complex steps and in reality is worth far more than the weaver’s asking price!